The co-owner of Noble Rot magazine and the London restaurants of the same name, alongside Mark Andrew MW, exemplifies a new direction in wine writing and the enduring fascination wine holds for brilliant minds from other fields.

Born in Watford (Hertfordshire) in 1975, he studied art at Manchester Metropolitan University, where he started a successful career in music promoting club nights. After moving to London in 1996, he worked as a talent scout for A&M Records, later becoming head of Artist & Repertoire at Parlophone Records, where he signed artists like Coldplay and Lily Allen. In 2006, he was appointed managing director of Island Records.

In 2013, he made a radical change of direction by co-founding Noble Rot magazine with Andrew. With its pop-inspired covers, the publication adopted a playful, irreverent tone while reflecting the pair's enthusiastic exploration of regions, styles, and producers. This approach felt closer to the experiences chronicled by American importer Kermit Lynch in his late 1980s book Adventures on the Wine Route than to the coverage typically found in most English-language wine magazines at the time.

Writing was nothing new for Keeling, who had previously contributed to music publications such as Melody Maker and Jockey Slut. Noble Rot was an instant success and Keeling was named Drink Writer of the Year at the 2016 Fortnum & Mason Awards, having already won the Emerging Wine Writer award in 2015 followed by Food & Drink Writer at the Louis Roederer Awards in both 2017 and 2018.

The way the duo chose to support the magazine is also unusual. Rather than relying on advertising or hosting wine events, Keeling and Andrew opened their first restaurant in London in 2015, imbuing it with the same passion and exploratory spirit as the magazine. Two further restaurants followed, along with the wine import company Keeling Andrew and the Shrine to the Vine shops, which sell only wines they say they would genuinely be excited to drink themselves.

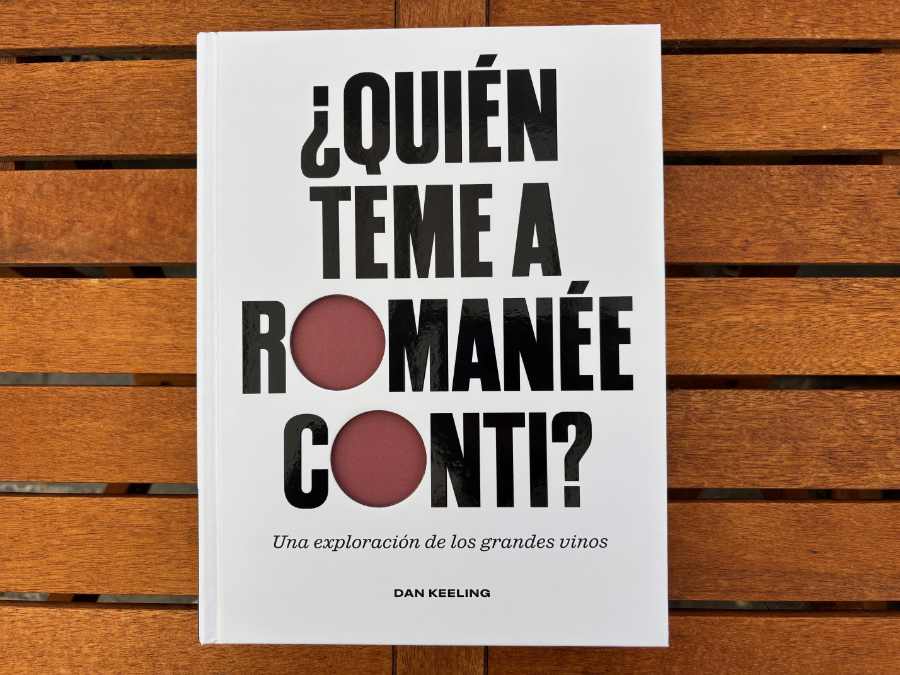

In 2020, the partners released Wine from Another Galaxy, a book partly drawn from articles originally published in the magazine. This was followed by Who Is Afraid of Romanée-Conti?, written solely by Dan Keeling. He visited Spain at the end of last year to present the Spanish edition, ¿Quién teme a Romanée-Conti?, published by Cinco Tintas.

The presentation took place at Los 33, one of Madrid's most popular restaurants, where Keeling felt completely at home. The event was attended by several Spanish producers represented by his import company in the UK, as well as others mentioned in the book. This interview, conducted immediately afterwards, has been edited for style and clarity.

You left a successful career in music to make a living in wine. Did you ever feel overwhelmed or have any doubts that you had made the right choice?

No, I didn't, although there were periods when I didn't have a pay cheque. Transitioning between careers is difficult. I had managed to save some money from my time in music, so I did have a cushion, but I also had two small children and a mortgage, and money was just going out the door. It was a great feeling the first time we paid ourselves in Noble Rot and that coincided with the opening of the restaurant. For the first few years we paid ourselves very little, but it was still money; it was a job.

You took your first wine course at Christie's, with Michael Broadbent and Steven Spurrier as teachers.

My wife and I got together in 2006. We were about to start a family and we couldn’t cook, so we went on a course at Leiths Cookery School in London. Being able to chop an onion is a skill British schools don’t teach —and they should. On the course, we became good friends with a music agent I vaguely knew and his wife, and we all signed up for a wine course at Christie’s, which was incredibly useful.

There were some classic, quintessential styles like Trimbach Riesling, which really smells of that petrol thing. My dad was a mechanic so that association of Riesling with petrol was the kind of thing that deepened my fascination through the course.

To build my knowledge, I took the WSET Advanced course and then the Diploma. My appreciation of Sherry, for example, and Champagne became a lot deeper through the WSET.

What are your views on wine education?

It is important that people don't go too much into wine education just for its own sake, in a purely academic way. Even when you start, you think that you do know a lot, buy you actually know nothing. That is why the term Master of Wine is a little bit absurd: the idea that you could master something as vast and as mysterious as wine. It is a little bit like a barrier; people can sometimes feel a bit inferior because there are these figures who supposedly know everything about the subject. I don't feel like that about wine. I feel I have a passion for it and I have explored wine a lot.

What is the secret behind the success of the Noble Rot restaurants?

The partnership between me and my business partner, Mark [Mark Andrew]. We have many things that overlap but many other things that don't. We share a sensibility for wine and our tastes are similar. Our sense of humour is similar too, but we concentrate on different parts of the business.

Mark is a Master of Wine, funnily enough, but he doesn't wear it like some do. He is very knowledgeable and a great teacher, so he does a lot of staff training. He handles the financial side and loves managing, so he is more internal looking on the company whereas I am more external, looking after the magazine, the storytelling part, the collaborations and the design.

Our people are our biggest asset and we have an amazing managing director called Ollie [Oliver McSwiney].

Do you manage to retain your staff?

They do stay a long time, but you cannot expect people to stay with you forever. Some go on to open their own wine bars or restaurants and that is a real compliment for us. We have had quite a few people who have become head sommeliers at top restaurants in London. Jeri [Jeri Kimber-Ndiaye], the head sommelier at Dorian, used to work for us. And Holly [Holly Willcocks] is head sommelier at Mountain, Tomos Parry's restaurant in Soho.

Many people who were one generation up from me cite Oddbins* as the reason they got into wine. And I hope that we can do a similar thing in a contemporary sense.

As a magazine, Noble Rot brought fresh air to wine communication, but is it profitable on its own?

It is hard to quantify because we don't look at it as a profit-making enterprise. It is more about the force and the community. Every issue galvanises our community. If we wanted to make it profitable, we would do it differently. We would have advertising, sponsorship and stuff like that, but we choose to keep it free from all kinds of influences, and that makes it more personal, I think. And of course, it opens doors for us. We have picked up very good winemakers who have been readers of the magazine. It is really important, but it doesn’t turn over a lot of money.

So, you are both a wine writer and part of the industry.

I do think about who we write about in the magazine, not always focusing on the winemakers that we import. Of course I do write about them, but it must be in balance with lots of other stuff. We don't want it to be too silly. It needs to celebrate wine and food culture.

How many copies do you print?

12,000. The UK is the biggest market, but it also has a good audience in the US and elsewhere. I don't know how many we sell in Spain but there are a few stockists in wine shops, newsagents and bookshops.

How do you approach the future as an editor in an age of digitalisation, information overload and so many competing sources of information, particularly wine influencers in social media?

There are people who have influence and done different things, but the most important thing is to tell the story from your own point of view. You can get information from ChatGPT, but AI cannot give you a reason, and if it does it is not grounded on experience.

You must make it personal to yourself for other people to be interested, and try to write as clearly and effortlessly as possible to get over those ideas.

Wine has undergone profound changes over the last 20 years. Which has changed more: the style of the wines, or the way we talk about them?

Both. The way we talk about wine has changed because of online and social media. And wine itself has changed immensely and in many ways for the better. Finesse is a word that I have used for most of the wines in the book.

Do the wines that people choose reflect an ideology of taste?

Yes, but some people haven't got their own taste, so they follow others. There is a lot of insecurity around wine. I think that's why Robert Parker was so successful. His scores gave people some certainty in something that is inherently uncertain.

When I see old Parker scores now, I use them as the exact opposite of someone who has a different taste to me. Some people like big, powerful wines. A friend of mine who writes for the magazine, John Niven, says that if a wine is under 14,5% abv it feels weak to him. That is his taste, and it is cool too.

You can make a big, powerful wine with finesse. I wrote recently about a domaine called Gour de Chaulé in Gigondas. The young guy who has taken over this 100-year-old estate uses Grenache, a tiny bit of Mourvèdre and Syrah to produce a big Gigondas with finesse and complexity. It is really exciting that people are pushing the boundaries of winemaking.

What do you think about wine scores?

If I were buying a 50-year-old claret and spending a bit of money on it, I would check Cellar Tracker reviews from people that I know or have similar tastes and look in the commentaries for incidents like cork taint.

But the idea that a score is a definitive thing giving certainty on something, is very vague. For me, it is simply a gauge of how much somebody likes something. So, if someone gives a wine 100 points, it just means they really like it. I am not adverse to scores, but I don’t use them myself. When I taste with winemakers, I use asterisks: three means that I really love a wine; two means it is great; and one that it is a step up from average.

Your book moves between celebrating the privilege of having tasted many of the world's greatest wines and advocating for high-quality wines to be made accessible to a wider audience. Isn't this contradictory?

The thing I dislike most about wine culture is barriers. It is not like music. You can go on Spotify and listen to all of Beethoven’s symphonies or the Rolling Stones’ catalogue; anyone can do that. But not everyone can taste Romanée-Conti, of course.

These wines are elitist because only a small percentage of the population will ever buy or taste them. Even if you had the money, would you spend £15,000 on a bottle? But great winemakers also make affordable wines, and that really interests me. You can buy Commando G's entry level wines, or Ramiro Ibañez’s wines, which aren’t expensive either, Suertes del Marqués’ Trenzado or Artuke Tinto which sells for under £10 [in the UK]. It is a great skill to make a wine like that.

Are you worried about the global decline in wine consumption?

I could not care less. People are drinking less of the commercial, branded stuff that is the equivalent of ready meals in supermarkets. I am not against good cheap wine. You can go to Marks and Spencer and get a decent bottle —not something to talk much about; made by a bloke in a factory—, but perfectly digestible. By contrast, artisanal, traditional wine has never been in a better place in terms of interest and accessibility.

You have written that Spain has become the world’s most interesting wine country. From your point of view, what is the most powerful story Spain has to offer to the world?

There are so many. I have been writing about Sherry again. I don't know if it will ever regain popularity. It has this strange flavour that you must acquire. It is like tasting lime pickle in an Indian restaurant or trying olives or anchovies; you don't necessarily start off. It freaks people out, I guess.

But if you are into wine, into flavour and into stories, then it is amazing. For example, I love the wines of Equipo Navazos; they are such good value and have so much intensity and complexity. If you were to buy the equivalent in Burgundy or Bordeaux, you wouldn’t get it for €30. Sherry is a truly great story.

I was in Tenerife last week and I love that story too. Two hundred years ago, British ships stopped there for supplies. In the 1600s, 15 million litres of wine were being shipped back to Britain. I love it when Brits think of Tenerife as a low-rent holiday place. And then you say: “You should try a wine from Tenerife.” And they think you are taking the piss out of then. Then, they try it and wow! These are some of the best wines in Europe, and in the world.

You devote an entire chapter to Priorat and another to the new unfortified wines from the Sherry region. You also mention the Canary Islands, the Ribeira Sacra area and Gredos. What makes these regions so interesting to you?

The fact that they are using native varieties is really interesting. The Spanish winemakers I know like Ramiro Ibáñez and Willy Peréz or Telmo Rodríguez are also big into history, as well as being out minded and not nationalistic. That really appeals.

I love seeing, for instance, how Listán Blanco from Tenerife, compares to unfortified Palomino from Jerez. Both come from the same vine but have different styles. What I love about Spain as well is that it is an outward-looking country. After a long time having to be in with Franco, it came out trying harder. Wine is the next wave of Spain’s amazing gastronomic explosion. Spain comes down to story, place and people, and it must come down as well to what is in the glass, which is brilliant.

What are the most obvious strengths and weaknesses of Spanish wine, in your opinion?

The strength is all the things that we have just talked about. There is that character identity and a great heritage that people has been perfecting quietly in the background while everybody else was looking at Bordeaux and stuff like that. Spain has emerged at a time when the Bordelais cannot sell new vintages because all the problems around en primeur. Knowing itself is a strength, but I cannot really think of a weakness.

Cheap, underrated wines, perhaps?

Cheap, yes, but not sure about underrated. If I think about our restaurants, we have got to have some bargains on our wine list so that we can offer a set lunch around £26 or £27 or whatever it is now. When prices went up during lockdown, some winemakers in France put all their ex-cellar prices up and now there are a few problems with this.

Spanish wine makers need to continue with what they are doing and price themselves well, building long-term relationships with wine drinkers and wine lovers to be with them for all their lives, so that they will always come back to. I remember drinking Commando G’s La Bruja Avería because that was what we could afford, and now we are drinking Rumbo El Norte. It is important to remain accessible.

*Oddbins was a leading UK wine merchant chain during the 1980s and 1990s. It was well known for its varied, appealing wine selection and knowledgeable staff.

Amaya Cervera

A wine journalist with almost 30 years' experience, she is the founder of the award-winning Spanish Wine Lover website. In 2023, she won the National Gastronomy Award for Gastronomic Communication

Cumal 2021 Red

NEWSLETTER

Join our community of Spanish wine lovers