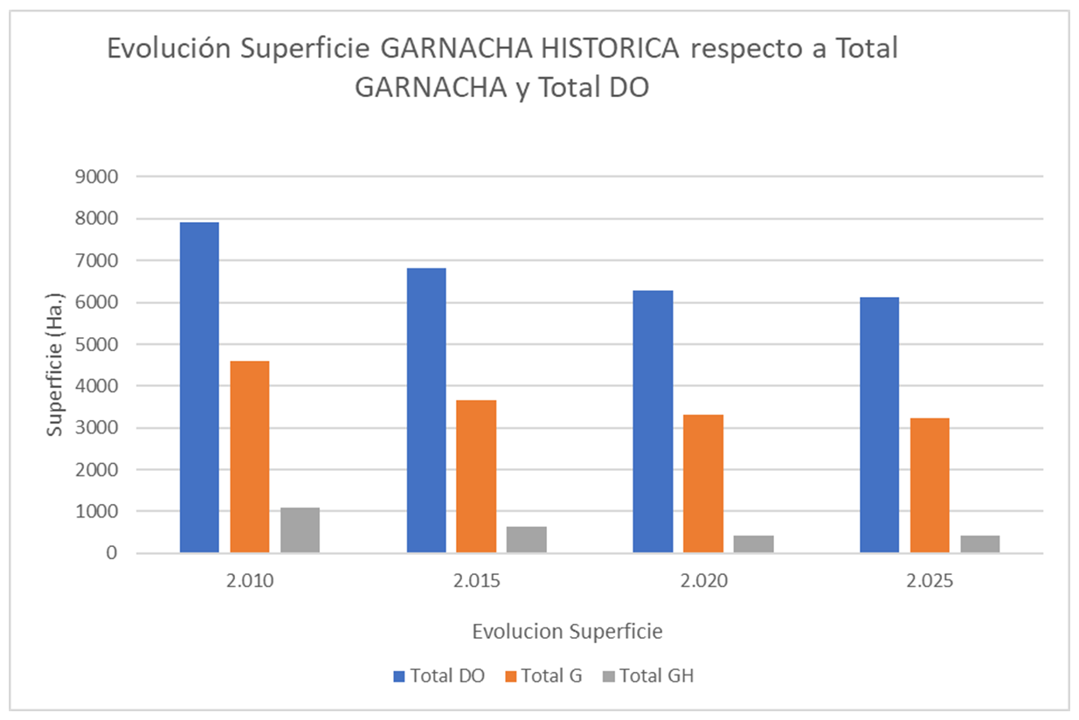

Between 2010 and 2025, the area under vine in DO Campo de Borja shrank by 22%, but the decline of its flagship variety has been even more alarming. Garnacha plantings fell by 30%, while old vines suffered dramatic losses of 60%. In the space of 15 years, the number of Garnacha vines over 35 years old has plummeted from 1,000 to 425 hectares.

“There is a striking paradox between this steady decline and the growing demand for wines made from old vines, both at trade fairs and among importers,” says José Ignacio Gracia, General Secretary of Campo de Borja Regulatory Board.

According to Gracia, the lack of generational renewal and the region's cooperative structure are the main factors behind the decline. Around 90% of the grapes are controlled by cooperatives, whose business model does not always guarantee prices that would sustain this viticultural heritage. Despite isolated efforts to stem the tide —the Fuendejalón cooperative, for instance, has safeguarded 150 hectares of old vineyards by leasing plots from members without successors— the overall outlook remains bleak.

This is why the DO launched the Garnachas Históricas (Historic Garnachas) project, designed to reverse the trend. The initiative consists of two research programmes led by the University of Navarra and the University of Zaragoza which aim, respectively, to develop a methodology for assessing vine age, and to identify the distinctive aromas and ageing potential associated with old Garnacha vineyards. Preliminary findings were presented a few weeks ago at The Old Vine Conference in California, a not-for-profit association that champions old vines on a global scale and includes DO Campo de Borja among its members. The research will ultimately support the creation of a protected category for regional wines made from vines over 35 years old, allowing them to be labelled as “Garnachas Históricas”'.

The problem with records

Determining the precise age of a vineyard is no easy task. Few owners keep reliable records of planting dates and Spain's vineyard registry was set up relatively late, following a requirement of the 1970 Wine and Alcohol Statute.

"Property registration is optional and, obviously, there is a cost involved, which is why many vineyards were never registered,” Gracia points out. “Appellations rely on data from Spain's vineyard register, which was compiled by the Ministry of Agriculture through surveying owners and was later transferred to the autonomous communities. Records from the last 50 years are reasonably accurate, but verifying the exact planting dates from earlier periods is much harder."

Many Spanish appellations accept the term "old vines" for wines made from +35-year-old vines, following the OIV’s recent recommendation. Priorat (Tarragona, Catalonia) takes a stricter approach, applying this category only to vines over 75 years old, verified by aerial photographs taken in 1945 and subsequent images from 1955, 1986 and 1995. Ribera del Duero allows the terms ‘centenary vineyards’ and ‘pre-phylloxera vineyard’, the latter reserved for vines planted before 1900. Documentary proof is required by the Regulatory Board, although as Alberto Tobes, head of viticulture, oenology and tasting panel, notes, such evidence is not always watertight.

By land and air

Against this backdrop, Gonzaga Santesteban, viticulture researcher and professor at the University of Navarra, set out to create a method for dating Campo de Borja's old Garnacha vines. “We realised early on that a single indicator wouldn’t suffice; we needed a probabilistic approach built on multiple pieces of evidence,” he explains.

Thus, aerial photographs were used to study planting patterns, particularly the tresbolillo system, which consists of interspersed rows forming equilateral triangles to ensure equal spacing between plants and rows; a common feature in old vineyards. Around 100 plots were examined using this method.

Genetic analysis, however, proved less revealing. “Variability was minimal, as 98% of the plants were Garnacha,” notes Santesteban. This is in stark contrast to his research in Navarra, where old vineyards typically include 10% of other varieties co-planted with Garnacha. Rootstocks were also examined, as they reflect the trends of different periods. Although occasional variations were found within the same plot, the most common rootstock was Rupestris de Lot.

The most significant contribution by Santesteban and PhD student Mónica Galar was their measurement of pruning growth over the past 10–15 years and its correlation with the plant's total height. Using a laser scanner, they built 3D images of each vine and measured annual growth with precision. They discovered that vines in Campo de Borja grow by an average of 1.55 cm per year.

The research was carried out on dry-farmed, goblet-trained vineyards owned by members of Bodegas Aragonesas, Ainzón and Borsao, and aged between 30 and 90 years or of unknown age.

“We have proven that it is possible to establish a methodology adaptable to different wine regions and varieties,” notes Santesteban. "The next step is to verify whether our criteria are appropriate for each area or whether additional factors should be considered.”

The presentation generated considerable interest at The Old Vine Conference. Beyond its practical application, it underscored the scale of vine loss in Spain and the need to preserve the unique characteristics of its wine regions.

What do old vines smell of?

The second Garnachas Históricas study was carried out with the Aroma Analysis and Oenology Laboratory at the University of Zaragoza, led by Vicente Ferreira. It examined the distinctive aromas of grapes from old vineyards and the ageing potential of their wines.

To this end, researchers compared the aromatic profiles of grapes from historic vineyards with those from adjacent young vineyards. To preserve primary aromas and ensure accuracy, the evaluation was conducted on fortified musts.

The findings showed that grapes from old vineyards display more intense phenolic aromas and tend to develop aromas closer to black fruit. Even more striking was the greater individuality of samples from historic vines, whereas young vine grapes showed far more similarity among themselves. Historic vines also contained a higher concentration of a particular group of aromatic compounds. “The bond that old vines have with the land is much more apparent,” Ferreira concluded.

Amaya Cervera

A wine journalist with almost 30 years' experience, she is the founder of the award-winning Spanish Wine Lover website. In 2023, she won the National Gastronomy Award for Gastronomic Communication

NEWSLETTER

Join our community of Spanish wine lovers