After five years of organic farming, the García family -owners of Mauro, San Román, and Garmón- began to wonder what more they could do to convey the essence of the regions where they worked. Initially hesitant about biodynamics, their outlook changed after meeting Ángel Amurrio, consultant and preparation at Entheos Bio. Encouraged by his insights, they took the leap in 2015. A decade later, they have certified 270 ha across their estates in Ribera del Duero, Toro and Castilla y León, and are now converting their new projects in Rioja (Baynos) and Bierzo (Valeyo), where they started with conventionally farmed vineyards.

"This has forced us to spend more time in the vineyard and get to know it better," explained David Cancela, the group's production manager, at a congress organised by Entheos Bio in early April. The event brought together international experts such as Jean-Michel Florin, Dominique Massenot and Jürgen Fritz.

Among the attendees were dedicated biodynamic producers and some influential figures in Spain. Ricardo Pérez (Descendientes de J. Palacios, Bierzo), who translated Nicolas Joly's seminal book Wine from Sky to Earth into Spanish in 2004, was present, as were team members from Peter Sisseck’s Dominio de Pingus. Sisseck began implementing biodynamics in 2000 with the help of Jérôme Bougnaud and released a Demeter-certified Pingus in the 2015 vinatge. Now a farmer in his own right, Sisseck keeps cows that produce 300,000 kg of compost annually —and he even makes cheese. Although he has stepped away from official certification, he insists he maintains “the same philosophy as always.”

Biodynamics views agriculture as part of a self-sustaining farm organism where plants, animals and humans coexist. Rooted in the teachings of Austrian philosopher and anthroposophist Rudolf Steiner in the early 20th century, many of its core principles —especially the alignment of farming tasks with cosmic rhythms such as lunar cycles— echo traditional agricultural wisdom. Building upon organic practices, biodynamics introduces a series of pre-dynamised preparations applied in homeopathic doses. The two most important are 500 (horn manure), often described as a "microbiological bomb" for the soil, and 501 (horn silica), which enhances the plant’s aerial part.

Seeking to move beyond the esoteric image of the past, the congress, according to Amurrio (in the photo below), aimed "to introduce the seriousness and rigour that biodynamics deserves".

A growing presence

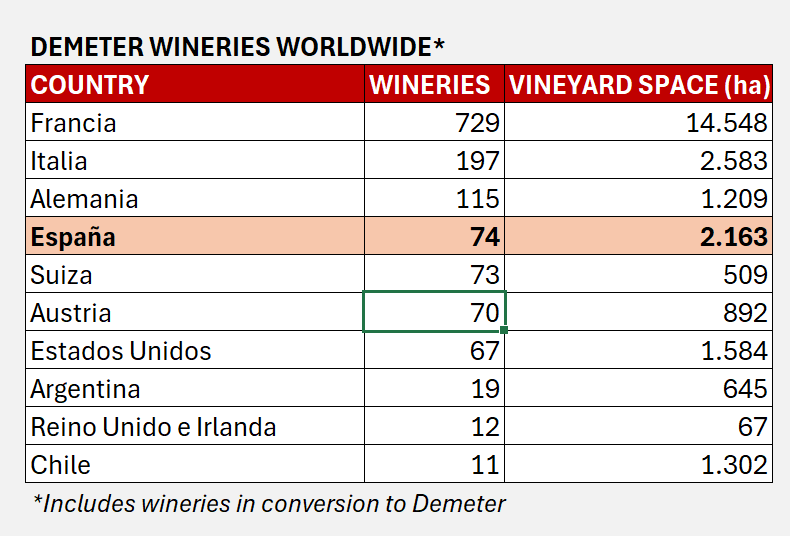

In Spain, biodynamics is very much a 21st century phenomenon. According to Demeter, the leading international certifier, only two wineries and 70 hectares of vineyards were certified in 2002. By 2010, with just two additional producers, the area had risen to 205ha. Since then, the growth has been substantial: today 3,500ha are certified, 28 wineries are certified for both their vineyards and wines, while 72 only certify their vineyards.

These figures place Spain among the most committed countries. According to the latest comparative study by Demeter International (using slightly different criteria, listing all entities as wineries), Spain ranks third worldwide in vineyard area under biodynamic certification —trailing only France and Italy— and fourth in terms of certified producers, just behind Germany. Among non-European countries, only the US and Chile exceed 1,000 certified hectares, with the latter having far fewer producers.

France's leading position in biodynamics is impressive, all the more so when one considers the area controlled by Biodyvin, the certification body dedicated exclusively to vines and wine (Demeter covers all types of crops) set up by the International Syndicate of Biodynamic Winegrowers. Although it has a handful of members in Italy, Portugal, Greece, Germany, Switzerland and Belgium, most of Biodyvin’s 215 members and 5,200 certified hectares are concentrated in France.

Interestingly, vineyards represent the principal biodynamic crop in Spain. As of 2024 they accounted for 25% of the certified area, ahead of olive groves (12%) and fruit trees (12%).

From disbelief to success

The experiences presented at the congress offered a valuable snapshot of biodynamics in Spain today.

One thing that became clear was that biodynamics can be applied successfully even across large vineyard holdings. Mauro alone manages 270ha, whereas the Torremilanos estate (Bodegas Peñalba López, Ribera del Duero), where the congress took place, has certified 200ha since 2014. But perhaps the most striking example is Aliances per la Terra, a collective porject launched by Gramona and its grape suppliers, which has amassed 500ha in a relatively short period of time.

Jaume Gramona has not shied away from the challenges. "People find it hard to understand why something that works has to be changed." His own shift began after meeting Claude and Lydia Bourguinon, experts in soil microbiology, in Burgundy. They opened his eyes to the lifeless condition of his vineyards in Penedès. "After that, it was logical to go one step further," he says. But he also warned: "Nowadays, if you don't farm organically, you simply don't exist".

Ernesto Peña’s story is another illustration of this transformation. A winemaker and vineyard consultant long committed to organic farming, he was initially resistant when asked to adopt biodynamic practices by the Chapoutier group in Spain. However, after training in France with the late Pierre Masson, a leading figure in the movement, he conducted multiple trials comparing pruning and preparations until he saw clear results in the vineyard and became convinced of the benefits of biodynamics. For Peña, one of the greatest achievements has been the reduction in vineyard treatments —and, in their particular case, the elimination of chlorosis in their Ribera del Duero vineyards.

Miguel Ángel Peñalba, vineyard manager at the Torremilanos family estate and a chemistry graduate, also had his reservations, but now admits that the process has been enriching: "I wouldn't go back.” As well as reducing both the number of dosage and treatments, he has seen marked improvements in soil health. "We have a lot of clay and it used to be very compacted. With biodynamics, the soil has changed colour, it looks whiter and now it’s easier to work".

Many vineyard managers highlighted the rapid impact of preparation 501. According to Mauro's David Cancela, "it gives structure and verticality to the wood and increases leaf mass." "The leaves are more upright and stronger", confirms Mario Cancho, head of viticulture at Milsetentayseis, Alma Carraovejas' second winery in Ribera del Duero, after only one year of using the preparations. They follow in the footsteps of other Demeter-certified estates in the group, such as Marañones in Gredos and Ossian in Segovia.

Taking the leap

Julián Palacios, vineyard consultant and founder of Viticultura Viva, also attended the congress. "The fact that major Spanish players are going biodynamic encourages us to learn and understand what's behind it," he said. What he most valued was the congress’s emphasis on the link between biodynamics and agronomy. For Palacios, "you can't do biodynamics well if you're not a good wine grower".

This was echoed by Fernando Mora of Bodegas Frontonio (Alpartir, Zaragoza), who is now moving into biodynamics. He views it as a form of "fine-tuning viticulture", without the need to achieve a "specific taste". Mora is particularly interested in the potential to observe and express "the best version of a place".

That, however, requires a fundamental shift in perspective. "We must not lose confidence in our ability to observe and understand. The big methodological change is to stop transforming nature and start trusting it," says Alejandro Muchada, partner of Champagne producer David Léclapart at Muchada Léclapart (Sanlúcar de Barrameda, Cádiz). Muchada adopts a highly meticulous approach: he leads a three-person team working just four hectares in Pago Miraflores. "You have to be willing to work and to invest. In conventional viticulture, one person can manage 10 hectares," he points out.

David Cancela, meanwhile, downplays the cost concerns when compared to high-quality viticulture. "Biodynamics is not more expensive, it doesn’t reduce yields and, once the equipment has been amortised, it is actually cheaper. The most important thing is that all the people involved must be committed, convinced, informed and well trained."

Rubén Jiménez, head of viticulture at Amaren (Samaniego, Rioja, soon to be fully organic), and Luis Cañas (projected to follow suit in five years) admits that they have been reading, tasting, attending events and generally following biodynamics with interest for years. They apply some herbal treatments but do not use the preparations. On a daily basis, they try to be respectful of the environment by promoting biodiversity, ecosystem recovery and co-planting. "Biodynamics is still a debate on the table," he says.

Much of the evolution of the movement in Spain will depend on the decisions taken by this and other producers and winegrowers. But what is certain is that biodynamics is generating increasing interest and less controversy.

Photo credits: A.C. y Entheos Bio

Amaya Cervera

A wine journalist with almost 30 years' experience, she is the founder of the award-winning Spanish Wine Lover website. In 2023, she won the National Gastronomy Award for Gastronomic Communication

Escolinas Mezcla Canguesa 2023 Red

NEWSLETTER

Join our community of Spanish wine lovers