"Rather than being a liquid that smells good, wine is a material that represents a place". This quote by legendary Burgundy producer Henri Jayer (1922–2006) was recalled by Jacky Rigaux, a writer, critic and researcher at the University of Burgundy, at an event held on 2 June at Gramona's estate in the heart of Catalonia’s Penedès region.

The aim of the gathering was to introduce Spanish professionals to the principles of geosensory tasting, a practice which places less emphasis on olfaction and instead focuses on mouthfeel and the sensations wine evokes on the palate.

The seminar brought together a group of French experts from diverse disciplines, including geology, neuroscience and wine tasting, who guided attendees on a journey of textures, salivation, flavours and aromas perceived in retro-olfaction.

Living soils

Many of the principles that Rigaux developed through his exchanges with Jayer speak directly to challenges faced by quality-minded producers, particularly the need to fully understand their terroirs and produce wines with a distinctive character. Geosensory tasting is presented as a tool to deepen the knowledge of vins de lieu (wines of place).

It assumes a respectful relationship with the land. Geologist and palaeontologist Georges Truc, who has devoted his career to studying the Rhône Valley's geological formations, explained that a plant's ability to absorb water and minerals from the soil depends on a symbiotic relationship between its roots and mycorrhizal fungi , whose microscopic filaments (hyphae) make these elements available to the plant's roots.

According to Truc, the hyphae convey the characteristics of the soil, but only in well-aerated, living land that is free from herbicides and other chemicals harmful to microbial life. “Terroir emerges when the land is tended wisely and respectfully. It fades away when it is subjugated and degraded to anonymity,” he writes in Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Histoire géologique & naissance des terroirs. In this book, he also uses geosensory tasting to highlight the textures and traits imparted to the wines by the region's major soil types. At the Gramona event, he led a tasting with four Garnachas from the Rhône Valley.

The guild of gourmets

The term ‘geosensory tasting’ was coined by Rigaux in the 1990s, but its underlying principles go back much further. The French researcher traces the concept to the 12th century, when the revival of the wine trade saw the emergence of the guild of gourmets, expert tasters who verified the contents of casks. From the 16th century onwards, the tastevin — a small, flattened cup used for tasting wine — became widespread and was adopted as a symbol of the profession. Indeed, it remains part of the ceremonial attire worn by sommeliers at competitions and formal events.

The role of the gourmet, as documented by French scientist Jules Lavalle (1820–1880) in his book Histoire et statistique de la vigne et des grands vins de la Côte d'Or, continued until the French Revolution. However, it faded with the dissolution of the guilds and the rise of the bourgeoisie.

In the mid-20th century, the expansion of France’s appellation system ushered in a more scientific or sensory approach to tasting. This was intended to certify that wines from recently incorporated areas met the required standard. Its main proponent was Jules Chauvet, a chemist, producer and aroma expert whose sulphur-free carbonic maceration research later inspired the natural wine movement. In the late 1960s, Chauvet also helped design the INAO glass — the official tasting glass of the Institut National des Appellations d'Origine — whose narrowing shape concentrates aromas and which would become the international standard for wine tasting. Incidentally, geosensory tasting has its own glass, designed by Jean-Pierre Lagneau and Laurent Vialette.

Le Toucher du Vin versus La Nez du Vin

For Rigaux, the primacy of aroma in modern tasting is symbolised by Le Nez du Vin, a popular kit containing a wide variety of scent vials, including common wine flaws.

Rigaux himself once prioritised the olfactory aspect of wine. But his thinking changed during a Burgundy tasting with Jayer, who declared: "Wine isn’t meant to be sniffed — it’s meant to be drunk!" The remark marked a turning point. In 2012, Rigaux published La dégustation géo-sensorielle, and today, many distinguished producers follow his approach, including Aubert de Villaine in Burgundy, Marcel Deiss in Alsace, and Anselme Selosse and Pascal Agrapart in Champagne.

Geosensory tasting focuses on texture, how wines move on the palate, the expression of tannins and retro-olfactory sensations. Could terms such as 'luminosity', 'suppleness', liveliness' instead of 'acidity' or 'footprint’ versus ‘length' offer more accurante descriptors and engage wine drinkers in new ways?

The response to Le Nez du Vin is Le Toucher du Vin: a set of eight fabrics with a variety of textures, ranging from silk and velvet to tulle, burlap, and denim. The idea is to carry out comparative evaluations of how wines feel: its consistency, flexibility and perceived temperature. The set's creator, sommelier Cyrille Tota, was initially dismissed as eccentric, but now collaborates with numerous tasting schools across France. For Tota, touch is a universal reference. He cited a 2018 study in which experts and untrained consumers were asked to use tactile descriptors for a series of wines tasted blind. Surprisingly, there was a high degree of agreement across both groups.

The scientific basis

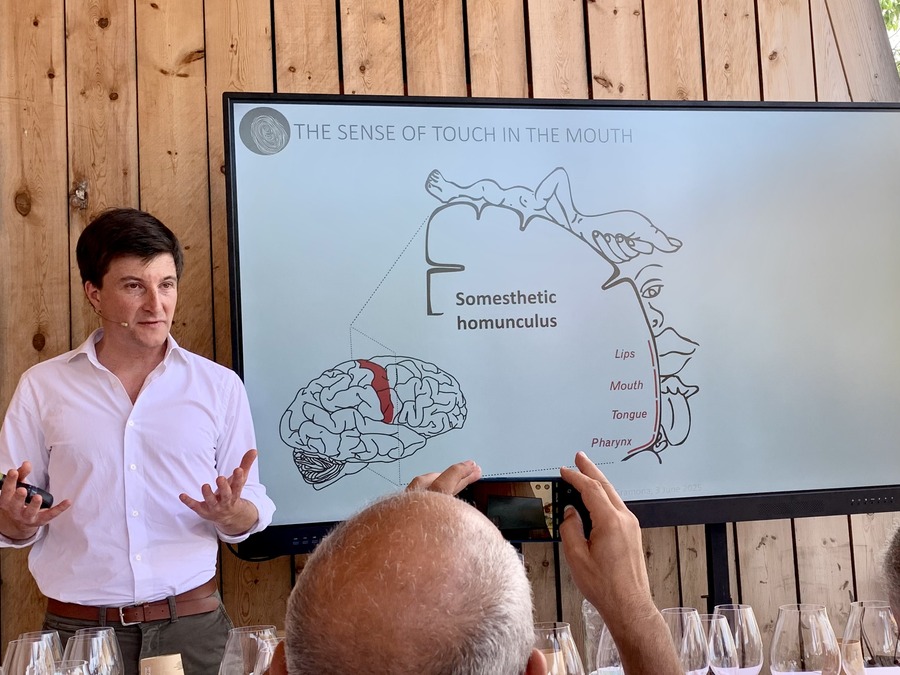

For Gabriel Lepousez, a neuroscientist specialising in wine-related sensory perception at the Pasteur Institute, geosensory tasting offers a new vocabulary. “Before the 1970s, there were hardly any aromatic descriptors. Today, 80% of the language of wine is aroma-based, with only 20% relating to other sensations. It would be interesting to redress the balance and embrace a more inclusive form of tasting,” he said. Lepousez presented some strong arguments, including the fact that around 20-25% of our tactile perception is concentrated in the mouth. He also emphasised salivation — humans produce a litre of saliva a day — and how saliva proteins interact with wine compounds to create different textures.

While much of his talk focused on sparkling wines, where additional CO2 plays a role, he also examined how taste perceptions unfold over time. Acidity and sweetness are perceived first; bitterness and umami follow and astringency appears last, as it requires interaction with saliva proteins. Recognising this sequence can help develop a more conscious tasting experience.

As the tongue touches the palate, we perceive what Lepousez calls “surface textures”: smoothness, roughness, dryness and granularity. As the tongue moves inwards, structural elements become apparent: density, weight, fluidity, viscosity and elasticity. Finally, tasters may even perceive a kind of geometric shape: spherical, vertical, pointed, compact or hollow.

According to Rigaux, it is easier to share what we feel on the palate than what we perceive through our nose.

Rigaux’s guide to tasting

For anyone familiar with conventional wine tasting —where sight, smell, and taste follow a set sequence— the hardest part of adopting geosensory tasting may be resisting the instinct to first dip one’s nose into the glass. Instead, Jacky Rigaux proposes four deliberate mouth-filling sips, each designed to explore a different sensory dimension. First, he reminds us that wine is a living substance originating from a specific piece of land, often one with a long historical identity, "where one or more grape varieties express all their complexity and energy."

Activation of the sense of touch. In the first sip, the wine is 'chewed' to stimulate the tactile cells in the mouth. This stage focuses on two elements: the perception of consistency and weight; second, the degree of energy the wine conveys. According to Rigaux, this energy is largely influence by the soil. Consistency may be perceived as sensations of warmth or coldness.

Additional tactile qualities include softness —the flexibility or pliancy of the wine— and texture (silky, velvety, astringent, etc.). The more delicate the wine, the more supple it tends to feel.

Activation of salivation. The second sip focuses on the salivation produced by the wine. Tasters are encouraged to concentrate and close their eyes. The salivation will differ depending on the nature of the soil and will impart a sense of viscosity (dense, fluid, etc.).

Activation of the sense of taste. The third sip reveals the flavours: liveliness (acidity), smoothness (sweetness), bitterness, saltiness and umami. "All taste constituents generate varying degrees of sapidity".

Activation of the sense of smell through retro-olfaction. The final stage involves gently drawing in air while swirling the wine on the palate to activate retro-olfaction. Thus, the aromas are approached after the tactile and flavour qualities of the wine have been experienced; with retro-olfaction, the aromas are amplified through salivation.

Only after this sequence does Rigaux suggest engaging in direct olfaction and visual assessment He also points out that sniffing must have been extremely difficult using the traditional tastavin with its shallow bowl and wide surface.

Amaya Cervera

A wine journalist with almost 30 years' experience, she is the founder of the award-winning Spanish Wine Lover website. In 2023, she won the National Gastronomy Award for Gastronomic Communication

NEWSLETTER

Join our community of Spanish wine lovers