Fighting phylloxera in the Canary Islands: urgent measures and a challenging harvest

Could the Canary Islands be facing the same pest that ravaged European vineyards in the late 19th century and early 20th centuries? Until a few weeks ago, the archipelago was one of the world's few phylloxera-free areas, where vines could still be grown ungrafted. The detection of several outbreaks of the destructive aphid in the northeast of Tenerife now threatens to change that.

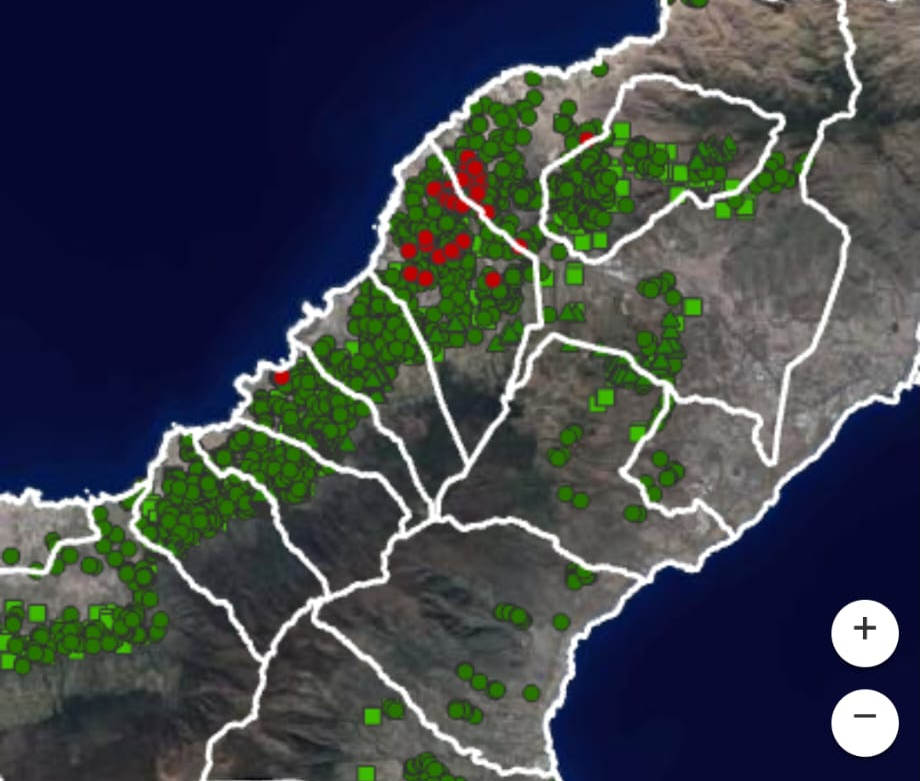

All the infested plants are in DO Tacoronte-Acentejo, with the most severe outbreaks reported in Valle de Guerra (Tacoronte) and La Laguna. Although it is too early to predict the eventual scale of the problem, the measures already adopted to contain its spread are affecting this year’s harvest and, in some cases, making grape picking extremely difficult.

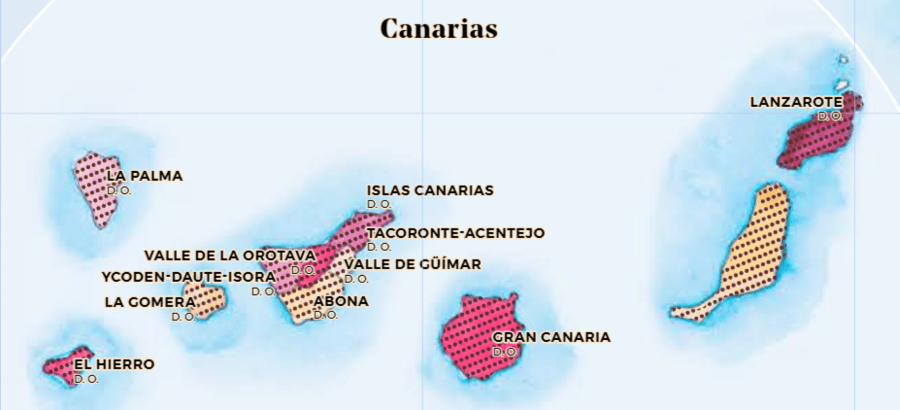

The Canary Islands’ Regional Council of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Food has banned the movement of grapes, plant material (including cuttings, vine shoots and rootstocks), and machinery or equipment (such as boxes and vineyard soil) both between islands and within different regions of the same island. The Spanish government has also halted the import and transit of grapes and grape seeds from countries where phylloxera is present, including mainland Spain. The only exception is packaged table grapes, which, according to local government technicians, do not pose a risk of spreading the pest. During harvest, grape movement is allowed under strict controls, provided that source vineyards are free form phylloxera.

Exhaustive controls

According to Santi Perera, senior agricultural officer and plant health specialist at Tenerife's council, the immediate priority is to monitor the harvest and prevent the plague from spreading. Technical efforts are therefore concentrated on controlling grape movements and conducting inspections. By the end of September, almost 4,400 tests had been completed, with just under 70 confirmed positive cases.

The producers most affected are those who process Tacoronte-Acentejo grapes in other areas of Tenerife, as the fruit cannot currently leave this region. This is the case of Envínate, which makes wine under the DOP Islas Canarias at the group’s winery in Santiago del Teide in the north-west, but sources grapes from Taganana, in the north-eastern corner of Tacoronte-Acentejo, for some of its most iconic wines. The ban forces them to destem and press, or vinify, on site before transporting must or finished wine, which pose no risk of spreading the pest. Grapes from vineyards located less than one kilometre from an infected plant cannot be moved outside the outbreak area. Movements of grapes between islands or unaffected regions, on the other hand, are only allowed once inspections certify that the grapes come from phylloxera-free vineyards.

AVIBO, the association of winegrowers and winemakers behind DOP Islas Canarias, has been particularly critical of the restrictions, as it is the only appellation that can source grapes across the entire archipelago. Its president, Juan Jesús Méndez of Viñátigo, describes the measures are unreasonable and absurd: “The limits on grape transit have been set by appellations [see map below]. Our proposal is to create a quarantine zone around each outbreak to prevent its spread and give the industry time to react.”

Loreto Pancorbo from Tierra Fundida, who sources grapes from various regions, believes that however disruptive, strict measures are necessary because if the pest spreads, many vineyards will be abandoned. "I have colleagues in La Orotava for whose vineyards are their only livelihood. Why put them at risk?" Yet she admits that the sector is in a state of upheaval. “Things were already very difficult with drought and high temperatures. This crisis has caught us unprepared — there has been no research into vine sanitation or rootstocks."

Meanwhile, for day-to-day operations the complications are significant. At Vinos en Tándem, grapes from unaffected areas of Tacoronte can still be taken to their winery in Los Baldíos (La Laguna), as can fruit from their vineyards in Los Realejos (La Orotava), provided the required inspections are carried out. “ With the grapes we grow close to an outbreak, we have arranged to destem at a local winery and then take only the must with the skins; the stems cannot leave the area,” Pancorbo explains.

Detection and treatment

The first outbreak was identified in a private garden in Valle de Guerra, where the owner noticed phylloxera galls on the leaves and alerted the local agricultural office. Laboratory analyses confirmed the pest the following day.

Subsequent cases were found in abandoned vineyards and, later in farmed plots too. On 13 August, the Canary Islands Government and the Tenerife Council announced that another outbreak had been contained in La Matanza, some distance from the initial hotspots. This time, the outbreak occurred in an avocado plantation bordered by old, abandoned vines. The plot, owned by Bodega Piedra Fluida, had been partially replanted with avocado trees from a nursery in Valle de Guerra a few months earlier, explains Loreto Pancorbo, who took the photo below.

When a case is confirmed, a containment perimeter of 500 metres and a buffer zone of up to one kilometre are established. All vines within these areas are examined, as well as neighbouring areas where vines are or were once grown. Infected plants are uprooted and destroyed on site. Roots are treated with systemic herbicide, soil is sprayed with insecticide and irrigated to improve absorption, then covered with soil and weed control fabric to prevent resurgence.

From leaves to root and back

So far, analyses show the pest is present only in leaf form.

Alfonso Lucas Espadas, a technical engineer with extensive experience at Murcia’s Plant Health Service and now adviser to Genoma Laboratorio, says that the pest can be introduced by adult specimens settling on a vine and mating, or by eggs laid in the plant's root system. One of the few Spanish experts on phylloxera, he has monitored outbreaks in Murcia’s table grape sector. “In recent years, climate change has favoured the lengthening of all pest cycles,” he explains. “In table grape cultivation, the reuse of land to renew plantations and continuous irrigation encourage phylloxera. Despite the use of American rootstocks, the populations are so large that they cause major problems.”

This resurgence is also affecting Vitis vinifera. “In Australia, the 1103 De Paulsen rootstock has lost its resistance. There is growing concern because once phylloxera attacks the leaves, the plant's physiology changes, leaving roots more vulnerable,” says Espadas.

Rafael García of Vitis Navarra nursery recalls the California crisis of the 1980s when the AXR1 rootstock lost its tolerance to the aphid. "Phylloxera is mutating and becoming more aggressive," he says. “Eggs are now being laid in mainland Spain, and galls have been found in our Moscatel de Grano Menudo collection in Navarra."

Phylloxera's ability to reproduce both sexually and asexually, and to survive in cold weather, explains its devastating power. Its life cycle begins with a fertilised egg produced by a male and a female. This may be a winter egg in the trunk’s bark before hatching in spring. The nymph reproduces asexually laying eggs in a leaf gall, producing hundreds of individuals that feed on the leaves or migrate to the roots [see photo below courtesy of Alfonso Lucas Espadas], piercing them for nourishment and creating swellings that allow other parasites to penetrate and eventually kill the vine. Winged forms may also appear, flying long distances to new sites where they lay male and female eggs and restart the cycle. Meanwhile, the root nymphs can hibernate through winter, resuming activity in spring.

Soil and climate play a key role in phylloxera’s spread. Moisture favours movement, while rain can disperse the insects further. They thrive in compact, friable soils such as the clays of Valle de Guerra, but rarely survive in dry, sandy soils.

Why now?

What kept the Canary Islands free from phylloxera until now? Isolation is part of the answer, though not the whole story —Madeira and the Azores, with similar conditions, did not escape. Jonatan García of Suertes del Marqués notes that commercial isolation was also decisive: Canarian wine production and exports declined in the mid-19th century, just before the pest spread across Europe.

The Canary Islands only gained strong phytosanitary protection in March 1987, when a government order banned the import of vine plant material. However, fruit and seeds were still allowed, until the Spanish government extended the ban to seeds in late August. Following the first phylloxera outbreak, Canary Islands Agriculture Councillor Narvay Quintero pointedly reminded Madrid that the islands had long been requesting more resources to combat illegal plant imports and strengthen port and airport surveillance.

“We believe phylloxera has always been in the Canary Islands, but soil conditions prevented its spread,” says Roberto Santana of Envínate. Carlos Lozano, technical director of Teneguía in La Palma and president of the Technical Association of Oenology in the Canary Islands, agrees: “It’s likely that to have been present for a long time, on all the islands. Now it has found the conditions it needs to develop, especially in neglected, untreated vineyards.”

However, María Francesca Fort, professor at Rovira i Virgili University in Tarragona, who has studied the archipelago's varieties since 2012, suggests a recent introduction, probably as a winter egg. This could explain why the roots are not yet colonised. This may never be known for certain, although most experts agree that the most likely cause is the arrival of illegal plant material.

Looking ahead

While wine lovers worldwide celebrate the unique character of Canarian wines, many locals see phylloxera as a potential final blow to winegrowing.

“In the last decade, we have lost half our land under vine. Vines are weakened by viruses, yields are falling and adaption to climate change is increasingly difficult," says Méndez, who stresses the need to renew plant material.

Worryingly, vineyard fragmentation and the lack of generational renewal are already leading to abandoned plots and could make replanting unfeasible. “Many smallholders would give up, meaning the loss of traditional systems such as cordón trenzado [on the photo below] or low trellises,” says García of Suertes del Marqués. He works in Valle de la Orotava, and his wines have gained international recognition in recent years. "One of the Canary Islands’ greatest assets is its ungrafted vines," he points out.

Even if outbreaks are contained and isolated, the challenges ahead are considerable. For Santana of Envínate, questions already loom : “If I can't harvest the grapes in Taganana and take them directly to the winery, it makes no sense to have two members of staff working there all year round.”

Pancorbo sums up the general feeling: "We need a plan for the future and ensure that winegrowing can be sustained in the long term, as well as measures to improve the profitability and viability of winegrowing in the Canary Islands."

Both AVIBO and the Technical Association of Oenology of the Canary Islands have called for a database of the islands’ unique grape varieties to preserve their heritage, and for urgent research into suitable rootstocks.

On 29 September, a scientific and technical committee was set up, bringing together researchers and technicians from regional and national institutions, alongside local organisations and international experts. The group includes specialists from the Canary Islands, mainland Spain and leading centres in Vienna, Bordeaux, California and Australia.

Amaya Cervera

A wine journalist with almost 30 years' experience, she is the founder of the award-winning Spanish Wine Lover website. In 2023, she won the National Gastronomy Award for Gastronomic Communication

Angelita del Challao 2021 Red

NEWSLETTER

Join our community of Spanish wine lovers