Jerez redefines itself: end of compulsory fortification and new DO

Despite a small harvest, with losses of up to 30% due to mildew, and the global decline in wine consumption, the Sherry region ends the summer with three pieces of good news that bring fresh hope to the sector: the end of the obligation to fortify wines, the imminent reduction of the minimum alcohol level for finos and manzanillas to 14%, and progress towards a new designation of origin for white wines made from albariza soils.

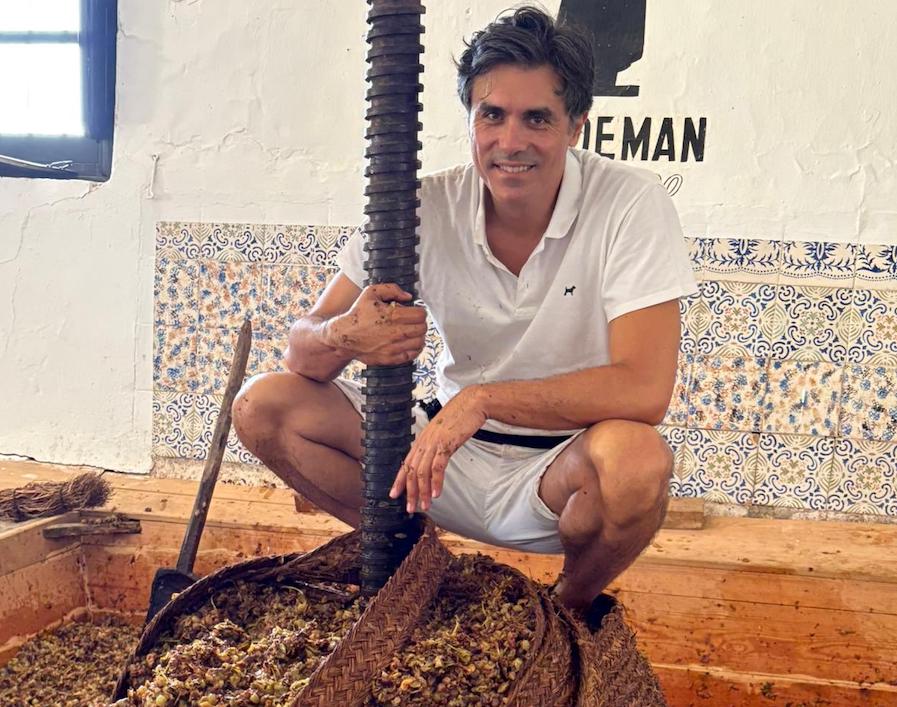

After more than a decade of “trials, errors, casks that turned to vinegar and much collective effort”, Jerez winemaker Willy Pérez —an outspoken advocate of shifting the focus back to the vineyard— has seen one of his greatest ambitions realised: Sherry wines can now be labelled as such without the need for fortification. The European Commission approved the change on 29 July 2025, and it came into force on 25 August following its publication in the EU’s Official Journal.

“We always dreamed of a Sherry that could simply be called wine, born of the vineyard and the albariza soils, without needing the ‘generoso’ surname,” Pérez wrote on Instagram. His first unfortified fino, La Barajuela, was released in 2013. “I have never been against fortification —it is part of our identity— but I was against the idea that a wine could not be called Sherry simply because it wasn’t fortified.”

Restoring the vineyard’s identity

The EU’s decision means that finos, manzanillas, amontillados, olorosos and palo cortados that naturally reach the alcoholic strength required by the Jerez-Xérès-Sherry DO will be classified simply as wine. These will coexist with fortified wines, which will continue to be considered generosos or liqueur wines, as they are today.

In its submission to Brussels, the Jerez-Xérès-Sherry Regulatory Board argued that current conditions—warmer climate, higher natural alcohol levels and the use of the traditional asoleo technique of sun-drying grapes before pressing them— make fortification unnecessary to achieve stable wines or the required sensory profile.

For Pérez, the change restores the vineyard’s central role: “We must remember that the most exported style of Sherry in the past was sweet, and it was fortified to prevent instability and refermentation. In finos and manzanillas, fortification had less justification; it was mainly done to stop the veil of flor from appearing in the bottles during transport. In a way, it was the preservative of its time.”

Alongside the technical arguments, the request to the EU also included bibliographic evidence and historical examples of naturally aged finos and manzanillas, some of which remain on the market today, such as Inocente, Tío Pepe and the manzanilla Conde de Aldama.

A step away from spirits

For decades, the association of dry Sherries with fortification brought them closer to spirits —at least in the minds of sommeliers, wine buyers and, indirectly, many consumers. Pérez, aware of the historic work done in the region to classify soils and vineyards, set himself the task of restoring the idea that dry Sherries are, above all, wines. “I saw that Jura occupied centre stage on the wine lists of the world’s top restaurants, while Sherry was pushed to the back. Sherry had been reduced to its fortified status.”At first, the idea was not easy to defend. Although he had strong skills and deep family roots in the region —his father, Luis Pérez, was professor of oenology and technical director at Domecq— the young winemaker suspected that reviving this style would be seen by some as an attack on fortified wines.

Fortunately, his friend Ramiro Ibáñez, a Sanlúcar-based grower and his partner in De la Riva, joined the cause. “In fact, De la Riva was created partly so we wouldn’t be seen as outsiders, but rather as two guys who love long-aged fortified Sherries as well. That’s a path that cannot be questioned. Our aim was to add another road, not to block the old one,” he explains.

It took time, but gradually the idea gained support among other producers, until the Regulatory Board submitted the proposal to the authorities. This request also included other, smaller changes —already in force since October 2022— such as the inclusion of new grape varieties, the expansion of the ageing zone to match the production area, and vineyard classification by pagos, among others. “The Council and its president, César Saldaña, deserve credit for being so open-minded,” Pérez acknowledges.

The quantitative impact of lifting mandatory fortification will be limited, since these wines require low yields and meticulous vineyard work. But a significant door has been opened: the chance to position more premium wines within the DO and the possibility of unfortified finos such as Bodegas Luis Pérez’s Caberrubia, which was outside the appellation, to be labelled as fino.

Lower alcohol levels

This historic step is not the only recent decision from Brussels. In February 2025, the EU also agreed that finos, manzanillas and pale creams can be marketed at 14% alcohol, down from the current minimum of 15%.The measure, which also applies to finos from Montilla-Moriles, will come into force once it is published in the Official Gazette of the Andalusian Government, a step that will allow the technical specifications to be updated. Saldaña believes this will happen soon. “The modification is in line with the en rama movement and reflects the desire to bottle wines that are as close as possible to what is in the cask.”

Reducing the level to 14% not only aligns biologically aged wines with market trends and cuts costs for wineries by removing the need to add wine spirit, but also confirms the findings of Innofino. This research project, driven by the Jerez and Montilla Regulatory Boards together with the universities of Córdoba and Cádiz and several wineries, demonstrated that lowering alcohol does not undermine the quality or sensory properties of biologically aged wines.

Albariza whites

Meanwhile, the region is moving forward on another major front: the creation of a new designation of origin specifically for terroir-driven white wines. The draft regulations are already on the table and will be debated at the September plenary session of the Jerez Regulatory Board.After three years of work, a group of producers of different sizes, origins and outlooks have defined, according to Saldaña, “the basic identity of these wines” —that is, the structure of the future DO, the grape varieties allowed, the zones and viticultural practices.

There is still no agreement on the name, although “Vinos de Albariza” seems to be the most popular. Nor has a decision been made on who will manage the new DO, although, as Saldaña notes, “it would make sense for the Regulatory Board itself to take on that role”.

If the plenary approves the proposal, the bureaucratic process —which must also include the green light from Brussels— will not be completed until at least 2027, Saldaña predicts. “This is a new DO, with a non-geographical name, which means extra work will be needed to prove that Vinos de Albariza is firmly identified with a specific area.”

Both César Saldaña and Willy Pérez, who is part of the working group and deeply enthusiastic about the new DO, agree that the hardest work has already been done and that broad consensus has been achieved across differing viewpoints. “Everyone accepts that these are not fruit-driven wines but wines of soil, of pago, of territory.”

Major wineries such as Barbadillo have accepted that high-volume wines like Castillo San Diego [labelled in recent years as Barbadillo Blanco] will be excluded, while more terroir-focused wines in their portfolio such as Alma de Balbaína will be included. For the president of the Board, the draft specifications are “sufficiently strict on yields to ensure that the positioning achieved by wineries in recent years is not undermined.” Being under the wings of an appellation, Saldaña concludes, will also encourage more consumers to discover the region’s wines. “This is the kind of boost the area needs.”

History suggests there is every reason to be optimistic. Pérez recalls a conversation with Dirk Niepoort, a key figure in the transformation of Porto and the red and white wines of Douro: “Dirk told me that when things changed there, nearly 40 years ago, the situation was very similar. Today, nobody questions those modifications.” For Pérez, evolution is part of the essence of Jerez: “I’ve seen it myself over the past 15 years and throughout history. A hundred and fifty years ago the veil of flor was considered a defect, and today you cannot understand Sherry without it. We must move slowly, avoid pressure and build together.”

Credits of César Saldaña photo and main picture: Abel Valdenebro

Willy and Ramiro’s landmark book out May 2026

Albariza. A New Renaissance is the long-awaited book that Willy Pérez and Ramiro Ibáñez have been working on for over a decade. In fact, it is not a single book but a five-volume series to be released in stages: two will be published in May next year, with the remaining three scheduled for 2027. Published by Abalon Books, the work, in the authors’ words, “explores the history, techniques and traditions that have shaped one of the world’s most iconic landscapes” and includes detailed profiles of more than 100 classified pagos in the region. The delay in its release —originally planned for 2025— was caused by the hundreds of illustrations and maps that complete the project.

Yolanda Ortiz de Arri

A journalist with over 25 years' experience in national and international media. WSET3, wine educator and translator

NEWSLETTER

Join our community of Spanish wine lovers