Ismael Álvarez: “Sommeliers should guide and inspire, never judge”

Ismael Álvarez (Tarancón, Cuenca, 1985) discovered wine at his grandfather Victoriano’s house —known affectionately in the village as Uncle Toria— among earthenware jars, grapes destined for the local cooperative, and vineyards with names like La Varastrela or El Pozo Mella. Some of these plots were set aside by his grandfather to make red wine for family consumption. It was there that Ismael first understood that wine was more than just a drink: it was work, tradition, and a source of family pride.

As a rebellious teenager who struggled at school, he often found himself grounded and spending his afternoons serving wine and beer in his parents' bar. “If you don't want to study, you'll have to learn a trade,” his parents used to say. For a while, he thought cooking might be his calling —but he soon realised his search wasn’t over. It was Paco Patón, then maître d' at Madrid's Hotel Urban, who gave him his first break in 2004 and changed everything with a single sentence: “You’re going to be a sommelier, and you don’t even know it yet.”

Since then, Álvarez has worked at acclaimed restaurants including Kabuki, Ramón Freixa and Nerua in Bilbao. He now oversees the wine programme at Michelin-starred Chispa Bistró, the Madrid restaurant opened in 2022 by Argentine chef Juan D’Onofrio. There, he curates a list of around 400 wines that reflect his personal vision. He’s also begun exploring the world of wine communication through his podcast, Catando Se Entiende la Gente.

In this conversation with Spanish Wine Lover, he speaks candidly about Spanish wine, wine service, how diners have changed —and the three kinds of customers he sees most today.

Is it true that you were given a World Atlas of Wine in English when you were just nine?

Yes! I didn't read the text but I was fascinated by the maps. I loved seeing that there were entire areas in France dedicated to wine, or tracing the hillsides and rivers in Germany. Discovering that wine could be made in the US really caught my attention —because when you’re nine, America seems like this far-off country with places like Hollywood and Disney.

So then when you eventually visited Burgundy, it wasn’t completely unfamiliar.

Perception changes completely when you visit a place in person. You can read, study, watch videos, look at photos… but until you set foot on the ground, you don't really grasp the scale or the character of a place. You can’t see the full picture.

Tell us about your grandfather; he seems to have had a big influence on you.

He used to tell me something that I have never forgotten. “There are no bad wines, only wines chosen at the wrong moments in your life.”

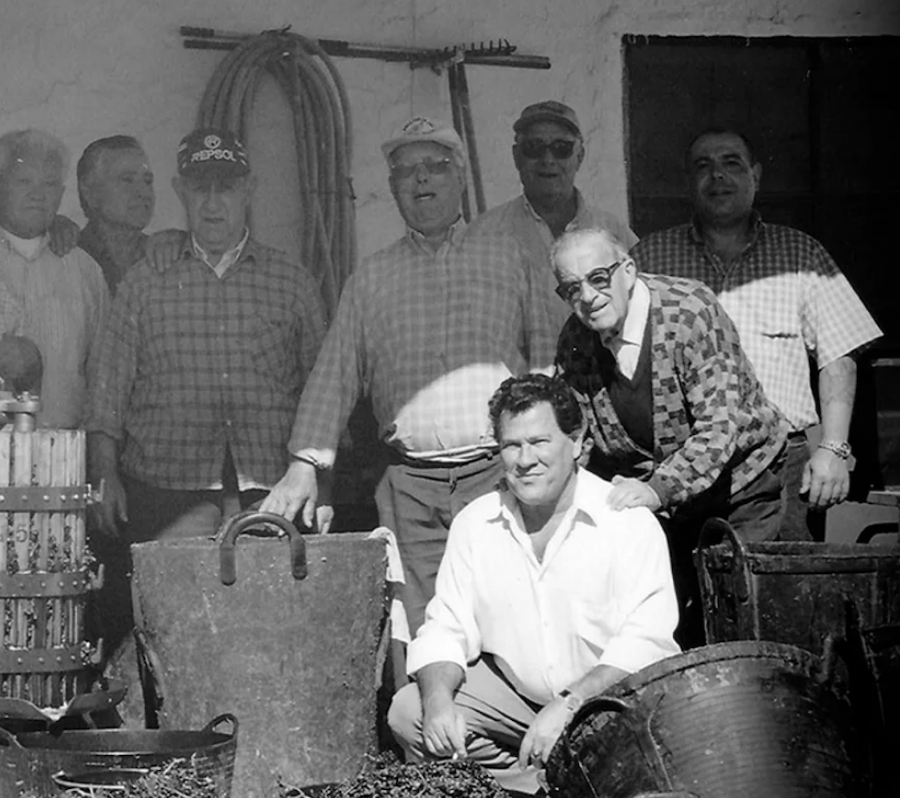

He (fourth, from left; Ismael's dad is the first on the right of the picture) always stressed the amount of work it takes to transform grapes into wine and to get that bottle to the table. Farming is thankless. Nature doesn’t negotiate. You adapt, and some years are full of joy —but others are years of sacrifice. We often pick the wrong wine not because it’s a bad wine, but because it doesn’t suit the moment.

Do you carry that lesson with you?

Absolutely. It’s something of a guiding principle for me. I know there are wines that aren’t for me —or maybe I’m not ready for them. But it’s not the wine’s fault. The effort behind every bottle deserves respect.

Have you ever refused to serve a wine because you thought the customer wouldn’t appreciate it?

In this profession we have tools to deal with situations like that. Bernat Voraviu said something interesting on the podcast: we sommeliers don’t need pans or fire —we only need words. Through context, we can give something more or less value. That’s my role: to provide context.

Can you give an example?

At Chispa, we have a selection of 1964 Riojas and other special bottles from Juan's father’s private cellar. We offer them at very reasonable prices —we’re not interested in speculation.

These wines catch the eye. A 1964 Martínez Lacuesta Gran Reserva for €150 is very tempting. But I always explain that opening one of these bottles is like starting a conversation with a 61-year-old. Just as you wouldn’t talk to a two-year-old the same way, you don’t drink a 61-year-old wine the same way. It depends on the kind of conversation you’re after.

What’s your take on alcohol-free wines?

To be honest, I view them with some suspicion. Alcohol is a natural part of the winemaking process. I’m not sure how much is left of the culture, the terroir, the tradition, when you remove it. I’m cautious, but it’s here, and we’ll see how it evolves.

What should a good restaurant wine look like?

I think it should be democratic, in the sense that it offers something for everyone —but without losing one’s identity. Sommeliers are no different to chefs. You wouldn’t go to Nerua if you hated vegetables. You wouldn’t eat at Umiko if you didn’t like fish. Or at Asador Donostiarra if you dislike meat. Sommeliers also have a style, it’s just that people rarely talk about us in those terms.

But that seems to be changing...

It is, slowly. But I can name five sommeliers with distinct styles, and many wine lovers wouldn’t know what they are. If I go to a restaurant where Alberto Ruffoni is working, I know what kind of wine experience I’ll have. If I go to my dear friend Silvia García at the Mandarin Oriental Ritz (pictured below, with Ismael), it’s something else entirely. We have our own identities, just like chefs. At Chispa, the cellar reflects mine. You won’t find wines there that go against my identity —because I wouldn’t enjoy opening them, and I don’t think the wines would enjoy it either.

So what is your identity?

Someone recently said something I really liked: “In a city like Madrid, where everyone fits, you’re too wild for the conventional and too conventional for the wild.” I like that. I’m comfortable embracing both without committing to either. I love some natural wines for their freedom and lack of constraints —but I also appreciate classic styles.

Who are some of your favourite producers?

I'm fascinated by Vicky Torres, but also by López de Heredia. They are two estates that really appeal to me and with which I identify in many ways. With Vicky, it’s her wild, intuitive way of understanding the vineyard and her obsession with capturing its spirit. With López de Heredia, it’s their absolute reverence for tradition.

How has the profession changed over the past 20 years?

We have much more information and it is more accessible than ever. Years ago, discovering certain wines or regions was hard; not everyone could travel and you had to have that vision of saying, ‘I'm going to visit Jura’. Now, with one click, you can discover a dozen Jura producers and buy their wines. Back then, we didn’t have importers like we do today.

How did you learn about wine?

I devoured the pages of El Mundo Vino. It was a gift to read Juancho Asenjo, Luis Gutiérrez and Víctor de la Serna. They shared their knowledge, their travels, their experiences and they talked to you about wines. It was one of the few wine publications around, and it was fascinating. We read it on the computer because in 2004, mobile phones didn't have internet!

And from a service point of view, how has your work changed?

I think we have become friendlier, more approachable. For a while, the world of wine felt like an exclusive club for super-knowledgeable people speaking a strange, alien jargon. The figure of the sommelier conveyed a sense of remoteness because he was a man dedicated to the study and analysis of wine, he wore a chain, a leather apron, lapel pins... It felt like an army colonel was coming to your table to ask what you wanted to drink and it was intimidating.

Now most of us have realised that the sensory part of wine is something intimate. As sommeliers, we’re tastemakers. Our job is to talk, recommend and persuade —but never to judge.

So a sommelier who talks about aromas, are they creating a distance?

I never talk about what a wine smells like. I prefer to tell the human stories behind the bottle —that’s what resonates. Thanks to better communication, we know the people and stories behind the wines. In the 80s or 90s, it would’ve been difficult to speak with the winemaker at Vega Sicilia. Now they come to see us, they open their wines, they share what they do and why. That helps us tell their story better.

Do you see yourself working as a sommelier until retirement?

I always tell Juan that this is my last restaurant. True, in the two and a half years we've been open, we\'ve laid a strong foundation. I'm increasingly happy because I see my identity reflected in the wine list. But this job takes a lot of energy. That’s why at Chispa we’ve made sustainability a priority —even in terms of work-life balance. We work four intense days, and then have three days off. It helps us stay connected to the outside world, which is so important.

And what would you like to do next?

I haven't decided yet. I can’t see myself working in sales. It’s tough, and I’d struggle to promote a portfolio where the bestsellers aren’t wines I believe in. It would feel like selling my soul a little. For now, I’m happy and at peace.

Are customers different now to when you started?

Generally speaking, they are quite territorial. What people drink in Bilbao, where I worked for ten years, is nothing like Madrid. In fact, I joke with Michael Wöhr, a German wine importer, who tells me: ‘this Riesling is too madrileño for you’, meaning it is denser, more powerful, with more sugar and less acidity. Since I have been working in Madrid, I often see three well-defined types of customers.

What are they?

First, there’s the statement-maker —someone who orders a Vega Sicilia to celebrate or impress at a business lunch. Wine as status. Then, there’s the curious one —eager to learn, explore, and try new things. And finally, the informed drinker —someone who already knows what they like and just needs a gentle nudge in the right direction.

As sommeliers, our job is to understand who’s in front of us. And the truth is, more and more people these days are incredibly well-informed —about wine, and about what it should cost.

Are there any producers or wines that are essential if you want to be at the cutting edge?

You have to know where to draw the line, but it’s tough —there are so many wines now, and allocations make it even trickier. Our wine list here is flexible and dynamic, but we’re thinking about creating a B list. We want to call it The Wines of Time, and it would feature those wines of which we only have two bottles —the kind we’ve taken off the main list because they would disappear in two days. The idea is to list them separately and just cross them off when they’re gone. It’s a bit of a vanity project, yes, but it’s also a way of saying: this wine has been here, it came and went.

Does Instagram influence wine choices?

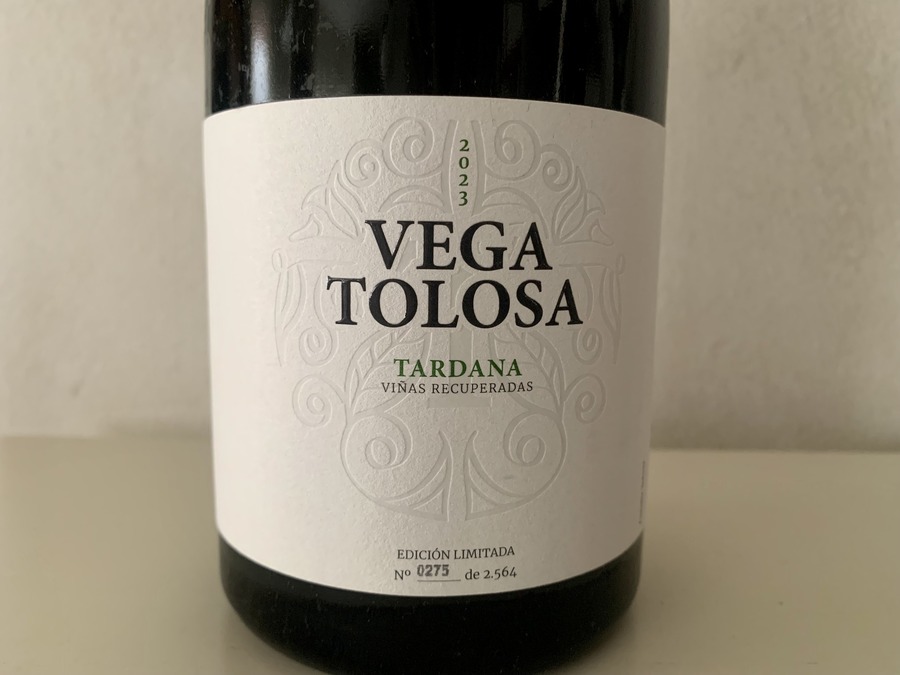

Yes —people often ask for wines they’ve seen on social media, sometimes ones we have opened at the restaurant. But that exposure can also backfire. There are guests who see a particular label so many times online that they assume it’s mainstream and skip it, even though only 15,000 bottles exist and I’ve only got 12. You have to embrace trends —but always with caution.

And what about natural wine? Is it a passing craze?

It’s a social movement. Natural wine is like reggaeton —a kind of rebellion, something young people embrace to break away from what their parents were into. When I left Madrid 12 years ago, there were no wine bars for young people. Now I can name over 15 natural wine bars where the under-30s go to drink. That’s wonderful.

Do you notice a drop in wine consumption at Chispa, in line with global trends?

Here we try to get people to drink wine —if not by the bottle, then by the glass. The menu’s short —11 dishes and three desserts— but all the dishes, including those on the tasting menu, are paired with wine. That means we’re pouring more than 16 wines by the glass, which rotate regularly, in a restaurant with just eight tables. The best thing? The place is always full and every table has wine on it. That makes me proud.

Is wine too expensive in restaurants?

I recently had dinner at a famous Madrid restaurant with an incredible wine list, but people were drinking beer because the wine was just unaffordable —and not just price-wise. At Chispa, I’ve got wines at €25 that I defend just as passionately as the €200 ones. If it’s on the list, it’s because I love it. Some people don’t want to spend much, but they’ll happily pay €25 and enjoy a good bottle of wine.

Is the ‘Burgundisation’ of wines just another trend, or a real shift?

Bear in mind that even Burgundy is seeing warmer vintages —there are wines with 16% alcohol now! But yes, I think there’s been a shift. When we talk about ‘Burgundisation’, we mean less oak, less concentration, less of that raisiny ripeness that pushed wines to such high alcohol levels they lost their identity.

Take Monastrell from Jumilla —I’m tasting wines with full maturity but incredible finesse. Or look at how Casa Castillo’s style has evolved. Las Gravas still has Mediterranean power, but it’s tighter, longer, finer, more delicate. And there’s much less oak now, too.

But doesn’t this risk diluting regional identity?

Nature is hard to homogenise, but it’s true —in Spain, we tend to standardise things, and that’s when identity suffers. At the same time, we’re seeing more respect for vintages, less over-extraction, less over-ripening —things that don’t help identity anyway. There’s more observation in the field, more vineyard work. That’s what matters. In Ribera del Duero or La Mancha, you barely see a soul in the vineyards. Go to Burgundy, and you see people in the fields.

Do you think standardised styles are being penalised by consumers?

Some people want their wine to taste the same every year. They want their marquis, their count, their ‘Señorío de’ whatever. If a vintage is different, they don’t like it —they’re after consistency. But those with a bit more interest in wine do start to reject that sameness.

Is that group growing?

Wine culture is definitely growing. People now have the confidence to ask for wines from the Canary Islands, for instance. But change is slower than I’d like. If you don’t nudge them out of their comfort zone, they go back to what they know —Rioja, Toro, Ribera. No one ever asks for something from the Sierra de Salamanca. I’d love for customers to push us sommeliers more. That would make us better.

There aren't many comfort zones on the Chispa wine list.

For example, I only have three Riberas and they’re not ones people recognize. The same goes for Rioja, but they are wines that are deeply rooted in their surroundings and terroir. It’s the same with Esmeralda García’s Verdejos. She says people don’t associate her wines with Verdejo, and that really winds me up. It’s like when a child is raised on strawberry yoghurt, strawberry ice cream, strawberry milkshake —and then you give them a real strawberry, and they don’t like it.

What excites you most about Spanish wine right now?

The sheer diversity. What does someone like Chicho Moldes of Fulcro in Rías Baixas have in common with Carmelo Peña in Gran Canaria? Or Carmelo with Tamerán? They’re on the same island, but their styles couldn’t be more different.

There’s a new generation capturing their sense of place, expressing that diversity, and it’s beautiful. I think we’re finally waking up to that in Spain. And we’re unbeatable on value. We just need to believe in what we’ve got —and talk about it.

What’s the balance of Spanish and foreign wines on your list?

‘Foreign’ is such a broad term. I do have more international wines than Spanish, but not more French than Spanish. Do I have more Spanish wines than German? Yes. That’s what matters to me. More Spanish than Italian? Also yes. I still champion Spanish wine more than any other.

Are most of your customers local or foreign?

Mostly domestic, but since the Michelin star we’re seeing more international guests. They want to try local wines —but also the international bargains. When I was at Nerua (pictured below), the French drank all the Burgundy because it was cheaper in Bilbao than back home! That’s changed a lot now.

And what do you like least about Spanish wine?

That the big wineries don’t embrace the small ones. Rioja wouldn’t be what it is without the big estates — they had the clout to put it on the map. Rioja is incredibly diverse, but it’s unfair to break it down into just three areas. I see at least ten. But in the end, it’s the big wineries that drive the DOs.

Now we’re seeing the concept of village wines.

That’s how it should be. Rioja is basically Spain’s Burgundy. What does a wine from Elciego have to do with one from San Vicente? Or Labastida with Laguardia? Burgundy is clear on that —the big and small producers are aligned. That doesn’t happen here.

Why do you think that is?

No idea. But it’s obvious the small producers aren’t the competition. The big estates got Rioja onto the world stage. The small ones add prestige. And some big names are showing that they can make five million bottles and still produce something special from a single plot. But they should be the ones pushing for differentiation at the Control Board. That can’t be left to José Gil or Roberto Oliván. The big players need to lead.

What do you value most in a wine? Ethics, aesthetics, the winemaker...?

I think it's a bit of everything. Ultimately, it has to appeal to my palate. Ethics matter —respecting the environment matters— but that has to be reflected in the bottle.

In a place like Chispa, wine should be hedonistic. It should bring you pleasure. Personally, I’m not swayed by a wine’s appearance —I care how it smells, tastes, feels. If that’s paired with a beautiful story, even better. But the story alone isn’t enough— otherwise it’s just incoherent.

What does modernity mean in wine?

Tough question! I’m not sure modernity really exists in wine, beyond label design. Wine is tradition, culture, rootedness —but it does evolve. For me, López de Heredia is a modern winery. In its day it was groundbreaking. Now it’s seen as classic. Modernity, to me, is about coherence between message and reality. It’s about respecting the end consumer, above all.

Can a bad person make a sublime wine?

Not for me. I’ve had wines I once loved —until I met the person behind them. Then I couldn’t enjoy them anymore. I can’t separate the artist from the work. If you are a bad person, your wine will be bad in the long run because you are bad. And I'm not talking about bad quality. You can be an attractive and beautiful person, but from the moment you reveal your wickedness, you cease to be attractive and beautiful.

I try to get to know the people behind the wines I sell. Though with some international names, that’s harder.

Have you ever stopped selling a wine for this reason?

Yes. The wines were delicious — but they weren’t good. That’s different. I punished them.

But it’s worked the other way too. There were wines I hadn’t appreciated —until I met the people. That happened with Viña Zorzal. Now I adore them.

What’s your take on wine education?

I’m not very academic —I don’t care for medals. I prefer learning by doing. Sure, the basics help, but you need to deconstruct them once you get going. I dislike WSET tasting sheets —they tend to standardise everything and could be applied to any wine. The best learning comes from travel, tasting, and building your own judgement.

Maybe we’d burst a few bubbles if we all did that...

I have opened Roulots that have been rubbish and I’ve posted the photo on Instagram and said nothing. We are quite unfair in wine —when something’s wrong, we stay quiet. But we should learn to speak up. Always respectfully, like my grandfather used to say. I think that helps to forge one's judgement.

I'll tell you a story. I was obsessed with trying Overnoy but when I asked Andrés [Conde Laya] from La Cigaleña to open a bottle for me, he told me it wasn't ready and I got really angry. One day he gave me a wine to taste blind and asked me what I thought. I saw things, but I couldn’t make sense of it. And he said, ‘look, it's Overnoy. See? You weren't ready’. And he was right.

Since then I've tried it a couple more times, but it's a wine I don't understand. And mind you, Overnoy is like the holy grail of wine, but it's not a wine for me. And you know what? It\'s no big deal.

You've started a podcast about wine. What is the aim of Catando Se Entiende la Gente?

It’s not about spreading wine culture —it’s about having fun with people I love and admire, tasting wine blind together. If someone gets something out of it, even better.

There’s a niche for this sort of podcasts in Spain. I’d love for it to reach more than just wine geeks. Imagine a lawyer hearing Jade Gross —she was a lawyer at the United Nations, now she makes wine— and thinking, “I want to hear her story.”

But let’s be honest, it’s a niche and few people listen to full hour-long podcasts. That’s why we also make short Instagram reels under 30 seconds —those actually get views.

What’s missing in wine communication? Do we need to dumb it down to reach more people?

I don’t think we need to dumb it down —we need to simplify and humanise the message. Talking about plots and exposure can sound remote. But say the wine comes from a hot, sunny place —that’s easier to grasp. If you also tell the personal story behind each bottle, people are more likely to listen.

And the million-euro question. How do we really bring wine closer to people?

It’s great that sommelier associations run tastings —but the real power lies with the guy running the bar on the corner, not with me. He sees 800 people a day. If he comes to a tasting, gets inspired, and makes a small change in his bar helped by us, he can shift the habits of everyone who walks through his door.

Albariza en las Venas in Jerez is doing that —democratising wine in a bar. We need one of those in every town of over 10,000 people.

Yolanda Ortiz de Arri

A journalist with over 25 years' experience in national and international media. WSET3, wine educator and translator

Pacio 2022 Red

NEWSLETTER

Join our community of Spanish wine lovers