On the verge of harvest, Spain endured one of its worst fire outbreaks in recent years, with wine-growing areas in Galicia and Castilla y León among the hardest hit.

Once the flames were extinguished, the task turned to assessing the damage. Some vines were burn or stripped of foliage, others bored raisined bunches. But what of the seemingly healthy grapes that looked fit for winemaking? Over them hung the threat of smoke taint.

Gonzalo Celayeta, a producer from Navarra and technical director of the San Martín de Unx cooperative, knows all too well how smoke taint seeps into grapes and imprints wines with unpleasant burnt, ashtray-like notes. In 2022, 2,500 hectares burned in this village in the Baja Montaña. The fire spared only the vineyards, leaving behind a landscape of green patches of vines among the charred black expanse (see the photo below). Numerous batches of wine were compromised.

“We had to discard around 800,000 litres of wine. After fermentation, nothing seemed amiss, but within days a smoky character emerged, often very pronounced." I can vouch for this unpleasant, charred flavour and rough texture, as Celayeta made me taste some samples during a visit to the area a few months after the fire.

Smoke taint is caused by volatile phenol compounds released when wood burns. Carried by the wind, they may cling to the bloom of fruit or be absorbed through the leaves, later passing into the berries. Their impact is not immediate: berries neutralise these compounds as a defence mechanism by binding them with sugar to form glycosides. Problems arise when glycosides are broken down by hydrolysis, a process which occurs naturally in wine, releasing the undesirable compounds. This process takes place slowly, often after fermentation and during ageing or even after bottling, and can continue for two to three years after harvest.

The severity of Navarra’s 2022 fires led the regional government's Viticulture and Oenology Section to partner with Excell Ibérica —the only laboratory in Spain to carry out smoke taint tests— to investigate the problem.

How smoke taint is assessed

Antonio Palacios, manager of Excell Ibérica, explains that analyses can be done on grapes, grape juice or wine. First, free volatile compounds are measured, but the key is assessing the potential for smoke taint. This is done through forced hydrolysis to assess the compounds that might be released at a later stage. “The advantage of testing grapes is that if the potential is very high, the decision not to pick the grapes can be made,” explains Palacios. “Testing must, on the other hand, enables preventive treatments, which are preferable to treating the finished wine.” Each sample costs €145.

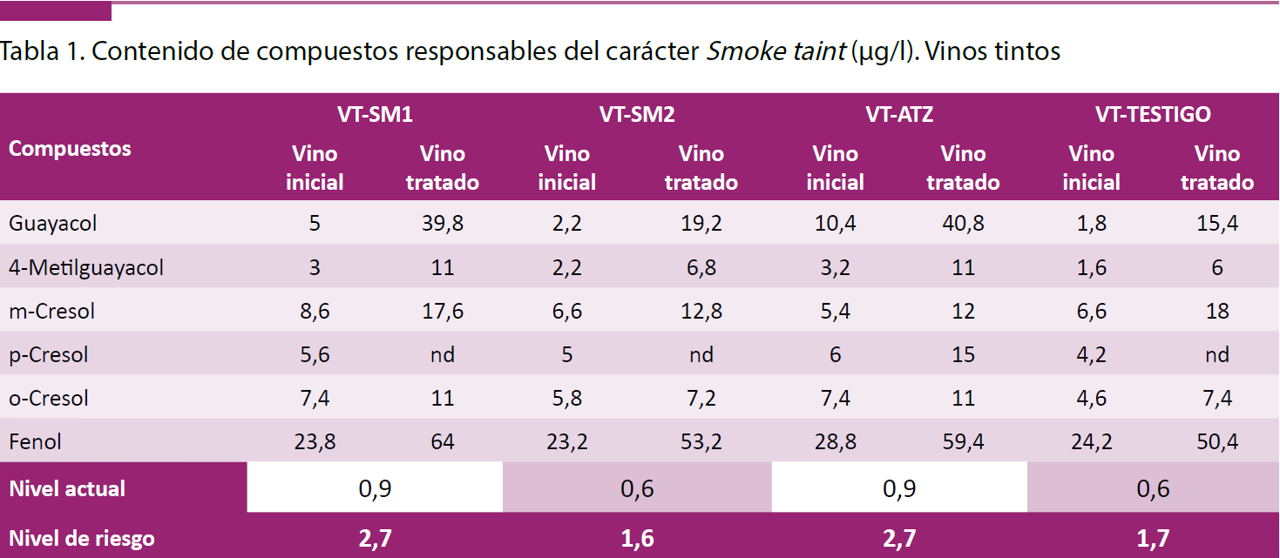

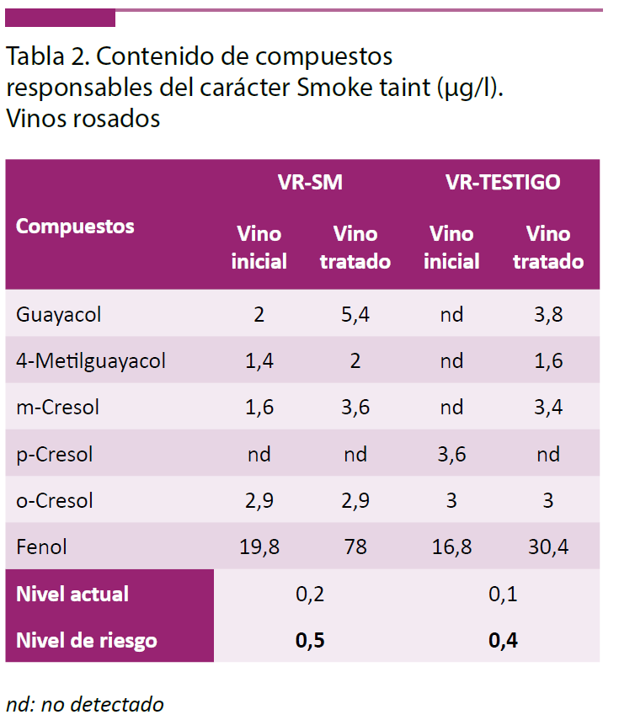

“It is not foolproof,” Palacios admits, “but the accuracy has improved significantly since we discovered that more than one molecule was involved.” The scope has now been expanded to include guaiacol, 4-methylguaiacol, m-cresol, p-cresol, o-cresol and phenol. A network of 14 labs from different countries is helping to validate, calibrate and refine the methodology, avoiding distortion and ensuring the accuracy of the tests.

The study conducted by Excell Ibérica in Navarra examined four samples of red wine and two of rosé, each paired with a control wine: an uncontaminated rosé from Evena and a smoke-free red from San Martín de Unx. While free volatile compounds alone did not indicate risk, hydrolisis revealed a marked increase in reds, even in the apparently sound sample. Rosés, however, remained below the tolerable threshold of 1 (see charts below).

In light of these findings, the Department of Rural Development and Environment of the Navarra Government introduced compensation measures. These were intended either to prevent wines with high smoke taint potential from reaching the market under the DO Navarra seal, or to allow producers to treat affected wines .

Smoke gets in the skin

Celayeta's experience with white and rosé wines was positive in 2022. There was no trace of smoke taint after fermentation or bottling, which supports the data provided by the analyses.

Reds, however, were a different story. “We selected very carefully, yet smoke taint still appeared in wines made from grapes grown outside the area affected by the fire, probably carried by the wind. It’s clear that the smoke is in the skins,” says Celayeta. “In 2022, we learned that maceration should be avoided or kept as brief as possible, and that rosé was the best option for affected grapes.”

This brings some hope for regions hit hard by fires this summer, such as Valdeorras and Monterrei, where white varieties dominate. Winemaker and consultant Pepe Hidalgo, who advises Guitián and O Luar do Sil in Valdeorras, is facing his third harvest affected by firesafter previous experiences in Empordà and Gredos. "A lot of preventive work can be done with white wines," he remarks. "Hand harvesting is crucial because leaves absorb smoke. Direct pressing and vigorous racking help too." During fermentation, Hidalgo recommends phenol absorbents such as yeast hulls, suitable even in organic winemaking. “Another tool is POF (phenolic off-flavour) yeasts, which do not generate phenols,” he adds.

The most common treatments for smoke taint in fermented wines are fining with activated carbon, though this can strip some of the wine’s intrinsic aromas, and reverse osmosis. Although more expensive, reverse osmosis is more precise and can significantly reduce unwanted volatile compounds. Also used for dealcoholisation, it employs nanofiltration membranes. Palacios describes it as a form of "advanced cosmetic surgery" that laves aromas intact.

The fires of 2025

Following this summer's wildfires, Excell Ibérica has received a surge of enquiries and requests to test samples. 'We are seeing strong demand from all affected wine¡ regions. It reflects the industry's commitment to consumers and its determination to avoid selling faulty wines," points out Palacios.

With an important presence in Monterrei, Martín Códax is one of the producers assessing the effects of smoke in their vineyards. “We are trying to understand these new generation fires, where flames and smoke often travel at great speed,” explains managing director Juan Vázquez. “So far, we have found volatile phenols and potential risk of smoke taint in vineyards in basins and valleys.” . This year, their strategy is to separate batches in order to identify those at risk and treat them accordingly.

Preliminary analyses, mostly on grapes and musts, suggest risk levels are lower than in Navarra in 2022, where fires were heavily concentrated in vineyard areas. “We have very few samples with high-risk potential,” Palacios confirms. "Levels of free volatile compounds are very low; most molecules are bound. This is why testing is so important to understand the real scope of the problem."

In fact, this practice looks set to become a standard among quality-conscious producers. In Bierzo, for example, vineyards escaped direct fire damage, but Ricardo Pérez of Descendientes de J. Palacios still tested his grapes. “In 2015, when La Faraona [the vineyard where the winery's top red wine comes from] almost burned down, there was no such option. I had to seek information in Australia and California because there was nothing in Spain,” he recalls.

These days, smoke taint is no longer a distant problem confined to other wine regions. It is here, in Spain’s vineyards.

Amaya Cervera

A wine journalist with almost 30 years' experience, she is the founder of the award-winning Spanish Wine Lover website. In 2023, she won the National Gastronomy Award for Gastronomic Communication

NEWSLETTER

Join our community of Spanish wine lovers